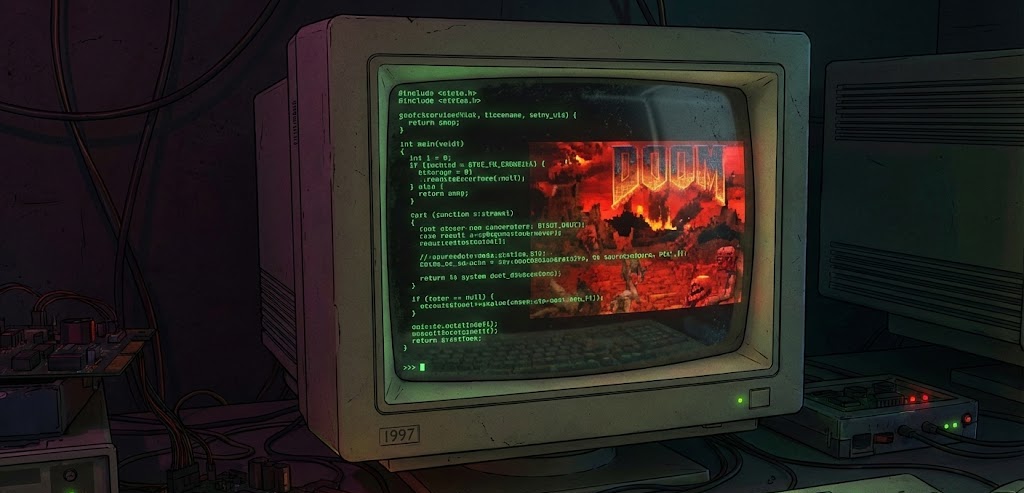

On December 23, 1997—Christmas Eve eve—John Carmack uploaded a file to an FTP server that would change the game industry forever. The DOOM source code, the engine that had redefined what PC games could do just four years earlier, was now free for anyone to study, modify, and build upon. It arrived with a note, characteristically understated: "I don't have a real good guess at how many people are going to be playing with this."

Tens of thousands, as it turned out. Then hundreds of thousands. The code would be ported to every platform imaginable: iPods, graphing calculators, ATMs, pregnancy tests, a hundred-foot jumbotron in Las Vegas. It would spawn an ecosystem of "source ports" that continues to thrive nearly three decades later. It would establish a precedent that id Software would follow with Quake, Quake II, Quake III, and Doom 3—each engine released to the public once it was five years old, like clockwork.

The real gift was permission.

The Hacker Who Made It

To understand why Carmack gave DOOM away, you have to understand where he came from. Not geographically—Kansas City, then Shreveport—but philosophically. Carmack was a child of the Hacker Ethic, that loosely codified set of principles that emerged from MIT's Tech Model Railroad Club in the 1960s: information wants to be free, access to computers should be unlimited, you should be judged by your hacks and nothing else.

"All of science and technology and culture and learning and academics is built upon using the work that others have done before. But to take a patenting approach and say, 'This idea is my idea, you cannot extend this idea in any way, because I own this idea'—it just seems so fundamentally wrong."

— John Carmack, as quoted in Masters of Doom

Carmack had lived this philosophy. When the source code to Quake was stolen and circulated underground, a programmer used it to create an unauthorized Linux port, then sent the patches to id. Most companies would have called lawyers. Carmack called it useful. At his behest, id Software adopted those patches as the foundation for an official Linux release. The thief had done good work; the work mattered more than the theft.

Both DOOM and Quake had been developed on NeXTSTEP, which itself ran on GNU tools. "I don't subscribe to all the FSF dogma," Carmack would later write, "but I have clearly benefited from their efforts." He was paying back a debt.

The Christmas Gift

The initial 1997 release came with restrictions—non-commercial use only, primarily because of legal complications with the DMX sound library that id had licensed rather than written. The Linux version was released because it had fewer entanglements. Bernd Kreimeier tidied up the code before release, documenting his changes in a changelog that itself became a teaching tool.

Two years later, on October 3, 1999, the restrictions lifted. After glDoom's source code was lost in a hard drive crash and the community requested a cleaner license, Carmack agreed to re-release under the GNU GPL. An email conversation was all it took. No lawyers, no lengthy negotiations—just a programmer honoring a request from other programmers.

"Programming is not a zero-sum game. Teaching something to a fellow programmer doesn't take it away from you. I'm happy to share what I can, because I'm in it for the love of programming."

— John Carmack

Carmack would later express mild regret about choosing the GPL over the more permissive BSD license—the copyleft requirement meant derivatives had to remain open, which he came to see as unnecessarily restrictive. But the choice didn't dampen the explosion that followed.

The Source Port Ecosystem

What Carmack released was not just a game engine. It was a Rosetta Stone for aspiring game developers, written in clean, readable C. The code showed how to do things that textbooks couldn't teach: how to build a renderer that ran fast on commodity hardware, how to structure a game loop, how to think about the relationship between visuals and gameplay.

Within months, the first "source ports" appeared—modified versions of the engine that added features, fixed bugs, or targeted new platforms. Today, the Doom Wiki lists dozens, each with its own philosophy:

Chocolate Doom (2005) aims for perfect authenticity, reproducing the original executable's behavior so precisely that it deliberately preserves bugs—including ones that crash the game. It exists to let players experience DOOM exactly as it was in 1993, warts and all.

GZDoom goes the opposite direction: OpenGL rendering, 3D floors, dynamic lighting, mod scripting so powerful that developers have built entirely new games on top of it. Some of those games have shipped commercially, the DOOM engine serving as invisible scaffolding.

Doom Legacy, Crispy Doom, PrBoom+—each port represents a different answer to the question: what should DOOM become? The community fractured not in acrimony but in abundance. Most serious players keep multiple ports installed: one for mods, one for vanilla play, one for multiplayer.

And then there are the novelty ports. DOOM on a thermostat. DOOM on a tractor's display. DOOM on a digital camera. The game has become a kind of "Hello World" for proving a platform is truly programmable—if it can run DOOM, it's a real computer.

The Quake Cascade

DOOM's release established the pattern. When Quake's engine followed in 1999, then Quake II in 2001, then Quake III in 2005, each release seeded new projects. The Quake engine, true 3D where DOOM had been a clever illusion, became the foundation for Half-Life. That lineage matters: Valve's Source engine, which powered Counter-Strike and Portal, descends from code Carmack gave away.

The Quake III Arena source code gave rise to ioquake3, a cleaned-up community fork that fixed bugs and added features while maintaining compatibility. Games like OpenArena, Xonotic, and World of Padman were built directly on id's open engines—projects that would have been impossible without corporate generosity that still has few parallels.

At QuakeCon 2007, Carmack confirmed the tradition would continue: id Tech 5 would eventually go open source too. "This is still the law of the land at id," he said, pledging to integrate as little proprietary middleware as possible to keep future releases clean.

Then ZeniMax acquired id in 2009. Carmack left for Oculus in 2013. Id Tech 6 shipped with Doom (2016), and no source release followed. The law of the land had changed landlords.

The Legacy

What did Carmack's gift actually accomplish? The easy answer is technical: thousands of programmers learned from that code, carried its patterns into their own work, built careers on foundations Carmack laid. The source ports ensured DOOM would never die—it runs on modern systems better than many games released last year.

But the harder answer is cultural. Carmack demonstrated that a company could give away the source code to its flagship product and not just survive, but thrive. Id Software continued to dominate the shooter genre for years after each release. The code they gave away was always old code; the competitive advantage had already moved on. What seemed like generosity was also good strategy.

"I was always a little disappointed that the example of id Software wasn't followed by more companies," Carmack wrote recently, watching another studio release vintage source. "Clearly, it was a Good Thing for us."

The game industry never fully adopted id's model. Studios remained secretive; engines stayed proprietary; the culture of game development diverged from broader open source norms. But the path was marked. The proof existed. And for a generation of developers who grew up reading that code, the hacker ethic wasn't just history—it was something a real company had actually done.

What Remains

In 2024, GZDoom development hit a snag: allegations that the lead maintainer had introduced AI-generated code, potentially violating the GPL. Developers forked the project into UZDoom. The drama was bitter, the stakes real, the outcome uncertain. But the fact that a fork was possible at all—that the code remained open for anyone to take in a new direction—was Carmack's gift still giving.

The DOOM source code sits on GitHub now, archived and starred by thousands. The original release note is still there, dated December 23, 1997: "If significant projects are undertaken, it would be cool to see a level of community cooperation."

Significant projects were undertaken. The cooperation continues. And somewhere, DOOM is running on a device it was never meant to run on, because a programmer who loved the craft decided that code should be shared.